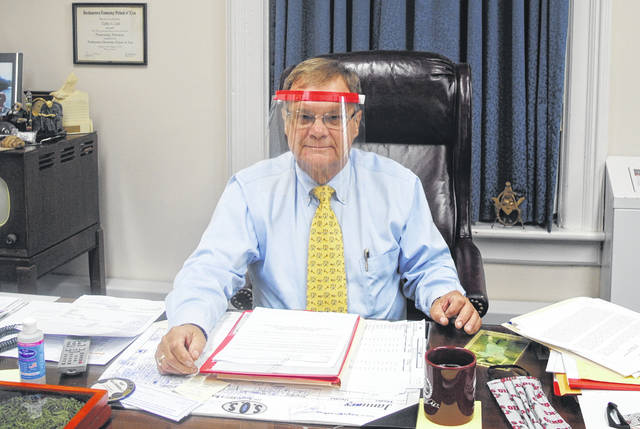

On June 5, the Highland County Common Pleas Court’s drug court met in-person as a group for the first time since March 3. Judge Rocky Coss and Tonya Sturgill, the director of programming and clinical services in the Highland County Probation Department, spoke with The Times-Gazette about the ways program leaders supported participants during quarantine and the program’s progress since it began nearly a year ago.

During quarantine, the drug court’s participants experienced a reduction in services. Participants were still drug tested, but some missed appointments for blood testing due to doctors’ cancelations or lack of transportation. COVID-19 also affected their medical assisted treatment — instead of a Vivitrol injection they received once a month, some participants switched to a pill-formatted treatment, which drug court program leaders have to rely on the participants to take. Participants relied on telehealth services to communicate with their counselors, and the probation department didn’t make as many home visits, instead connecting with participants through phone calls.

“The drug court people in Columbus have done a great job keeping in touch with all the drug courts and probation departments and offering suggestions for how to keep things going,” Coss said. “We missed one court session and then the next one we did by Zoom. [The participants] all have told us, unanimously I think, that they much prefer the in-person. We did drug court for almost three months by Zoom, and sometimes their reception wasn’t very good; some of them didn’t have computers and had to use their phones. It’s just not the same personal touch.”

Personal touch is one of the program’s defining characteristics. Though honesty and accountability play a significant role in the drug court program, Coss also focuses on positivity.

“I try to always be positive because one of the things we’re doing is building people up who have never been built up before. They weren’t raised in a family where they were recognized or their successes were rewarded. I always try to end up on a positive note, even with the people who are doing really bad,” Coss said. “It’s a really interesting dynamic. I wish more people could see how the interaction is. It’s much more personal, more informal. You get to know so much more about the offenders and what they’re doing and how they’re doing.”

Since July 31, 2019, a total of 31 people have been admitted to the program. Currently, the program has 23 active participants.

According to Coss, the drug court program is designed for 40 participants, who may spend between 18 and 24 months in the program.

“It’s not just treatment and probation — we’re also working with housing and getting people’s licenses reinstated,” Coss said. “We do have grant money to help people with that. We can even help people get things they need for work, like if they have to take a test or get a physical or need work clothes. We’ve helped pay a lot of reinstatement fees so people can drive because that’s one of the biggest impediments in rural areas: lack of transportation, not just for jobs but to get to their meetings.

“We’re trying to provide a complete toolbox for them to use. Really it’s still up to them. We’re the toolbox, and they have to decide to use those tools to build their recovery.”

Coss said the program also involves life counseling and can help participants learn how to budget.

He stressed that the program wasn’t designed for violent offenders or even first-time offenders.

According to Coss, drug courts are required to use the Ohio Risk Assessment System (ORAS) to gauge high-risk offenders. ORAS not only considers an individual’s criminal history and substance use, but also things like their family and social support, education and employment. Individuals are scored on a scale of zero through 40. In order to participate in drug court, an individual must score a 15 or higher.

“These people are harder to be successful because of their long histories, but most of them are sincere about wanting to change,” Coss said. “What I try to tell people is, ‘If you’re just trying to stay out of prison, go on regular probation. You’re not going to get screened as often, you’re probably not going to be as intensively supervised.’ They’ll pay their fees, and they usually get off in 18 months, but they’re still using.

“Drug court is going to be a longer, much harder commitment with much higher expectations, but if they do it in order to get sober, then they’re not going to be committing crimes, and they’re not going to go to prison. Community control is about staying out of prison; drug court’s about becoming sober and learning how to stay sober. That means people won’t be back.”

Reaching sobriety is no easy task, though.

“I’ve learned it’s a journey. The addiction, and dealing with it, is a permanent part of their lives. The thing to remember, particularly about opiate addiction, is that it is a medical condition,” Coss said. “Overall, I think we’ve been very fortunate. We haven’t had a huge number of relapses in our drug docket. We’ve had a couple, but that’s to be expected — relapse is a part of the recovery. Probably no one has ever gone into recovery and never relapsed. That’s one of the reasons it’s so dangerous, particularly with opiates, because if somebody relapses, and they’ve been clean for six months, eight months, or a year, and they decide they’re going to use and they use the same amount they used back when they were highly addicted, that’s when we see a lot of people overdose and die because their tolerance is gone.”

Coss hasn’t always seen addiction from that perspective, however.

“When I started out almost 12 years ago, I never thought I’d be a drug court judge. I had a much different view that if people are going to commit these crimes, they have to take responsibility,” Coss said. “I saw the same people over and over again, and I’ve learned that if I lock someone up, it’s just putting them on the sidelines temporarily, kind of like they’re sitting out for a quarter of the soccer game or the football game and getting right back in later.

“If we can help people become sober, productive members of society, they’re no longer being supported by society and being incarcerated and paying lawyers or out there overdosing and going to hospitals and using medical care provided at taxpayers’ expense — we can reduce those things. Now, we’re still using taxpayer money and grant money to provide some of these things, but it’s a lot cheaper. Studies have shown us that being in a drug court program is much cheaper than being incarcerated.

“We’re not going to be able to incarcerate our way out of this problem. This is a way of trying to break that cycle. We see people who are getting better, becoming tax-paying members of society, taking care of their children, and hopefully, reducing crime.”

Drug court sessions, which are held in the common pleas court twice a month, are open to the public. The next drug court sessions will be on Friday, June 19 beginning at 10 a.m. and 1:30 p.m.

Reach McKenzie Caldwell at 937-402-2570.