By 1898, the once-untamed and danger-fraught west had evolved into the fanciful Wild West, and Native Americans largely had ceased to be dangerous and were seen as romantic. Both had passed into folklore. Indeed, people in the Midwest and East were captivated by the romance of a phenomenon that actually had not been very romantic at all: the removal of Native Americans and the vanishing of their culture.

On Oct. 5 of that year, the Battle of Sugar Point was fought at Leech Lake, Minn. The 3rd U.S. Infantry engaged members of the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians in what has been termed as the last Indian uprising in the United States. While details of the conflict even today remain unclear, the results were hardly startling with the Indians being subdued and sent back to their reservation. Still, Secretary of the Interior Cornelius Bliss concluded that “the whites were thoroughly impressed with the stand taken by the Indians. In this respect, the outbreak has taught them [the whites] a lesson” – this was a far better outcome than was usual for the Native Americans.

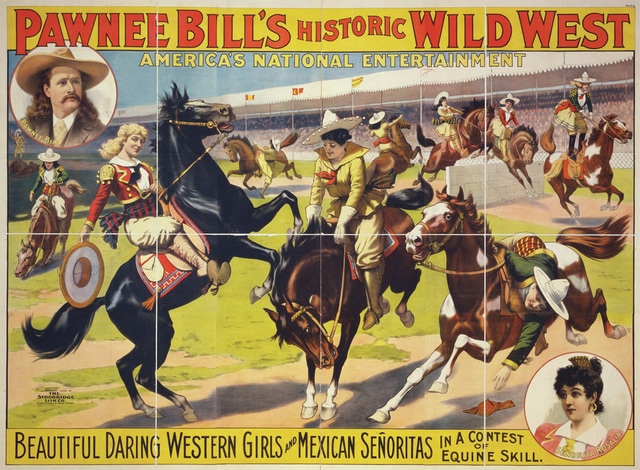

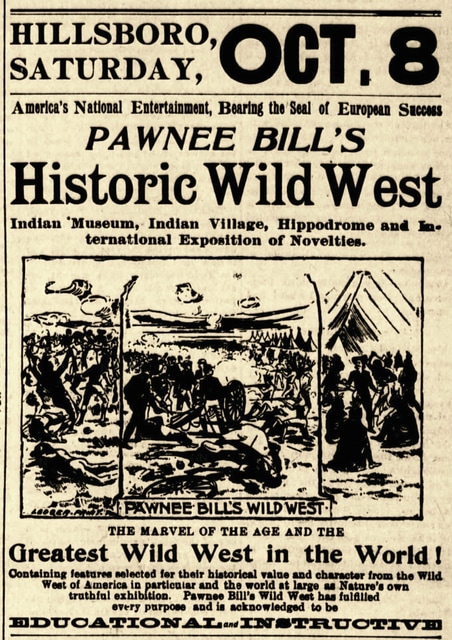

That same month, Hillsboro also was experiencing a taste of both the West and of Indians. On Oct. 8, Pawnee Bill’s Historic Wild West show came to the Highland County seat, replete with “beautiful daring western girls” and an accompanying impressive panoply of exciting acts.

Although a pundit for the Hillsboro News-Herald reluctantly had to confess that Pawnee Bill’s show was “not the equal of Buffalo Bill’s famous expedition,” he still enthusiastically, if ungrammatically, proclaimed it “super excellent.” The parade marching down High Street on that Saturday morning attracted a crowd so large that Hillsboro’s police force had to “make themselves useful” by keeping the streets clear so that the performers could pass.

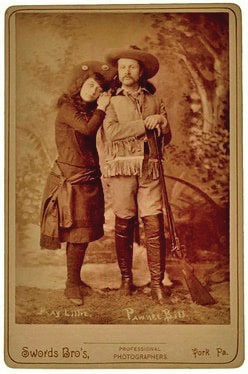

Pawnee Bill, who had been born Gordon William Lillie in Bloomington, Ill. in 1860, actually had worked on the Pawnee Indian Agency in Indian Territory (later Oklahoma). He then became a Pawnee-language interpreter for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In 1886, he married a young Quaker girl from Philadelphia named May Emma Manning. Lillie’s wedding gifts to his bride included a pony and a Marlin .22 caliber rifle. She quickly became adept with both.

In 1888, the couple launched their own Wild West extravaganza. Their first year was little short of a financial disaster, but the couple persevered and eventually their business flourished. The beautiful May starred as the “Champion Girl Horseback Shot of the West.” Accompanying her were a troupe of Mexican men and women, augmented by Pawnee Bill himself, who bore a striking resemblance to William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, appearing with a seemingly unlikely cast of Japanese performers and even a smattering of Arab jugglers. Still, the eclectic show was a great success and for years toured throughout the county prior to finally merging with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World in 1908.

The Hillsboro show goers that 1898 autumn, we’re told, were excited by the Mexican Hippodrome races and astounded by an historic re-enactment of the infamous and bloody 1857 Mormon Mountain Meadows massacre – surely an odd topic for any performance.

In addition, cowboys lassoed wild buffalo and Texas longhorns and May wowed the crowd with her considerable shooting skills, all the while riding and driving some 35 wild mustangs.

With the Spanish-American War just concluded earlier that August – Secretary of State John Hay called it “a splendid little war” – the United States’ triumph as a world power was assured. With a new century dawning, Americans could afford a moment of nostalgia and revel in the entertainment of Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show. Hillsboro ate it up.

Christopher S. Duckworth, a graduate of Ohio State University, spent three decades at the Ohio Historical Society, where he was founding editor of Timeline magazine, followed by another 10 years at the Columbus Museum of Art. Today, he owns his own publishing company, Brevoort Press LLC. He has deep Hillsboro roots – his grandfather, Edwin B. Ayres, owned W.R. Smith/Ayres Drug Company, and his great-great-great-grandfather, Peter Leake Ayres, built the Highland House.