Editor’s Note – This is the third in a new series of stories authored by Robert Kroeger, who has painted 23 barns in Highland County. The most recent 12 paintings, usually framed with actual wood from the barn depicted, will be auctioned off Sept. 24 when the Highland County Historical Society holds its annual Log Cabin Cookout. Proceeds from the paintings will benefit the historical society. Kroeger titled this story “Moonlight Gardens.”

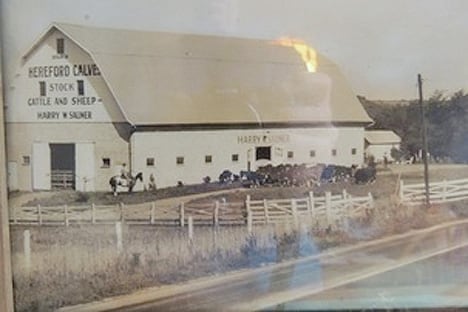

I’ll get to the title in a minute. First, let me tell you that this barn is massive. It’s a beast of a barn. But, in the summer growing season, if you drive by it on SR 73, just north of Hillsboro, you’ll miss it, thanks to an overgrowth of bushes, trees, and vines that camouflage it almost completely. The soil is fertile in Highland County.

But in April of 2016, on a day when the thermometer was closer to 32 than 92, we could see it clearly. And, it’s huge size, solidly anchored on concrete, not wood, show financial power. Whoever built it had money. Its concrete block lower level and sawmill-cut, not hand-hewn, beams hint at late 1890s or early 1900s. Unfortunately, its days are numbered, which makes me glad to have captured it – not only with oil paint on masonite, but also with a frame made of the barn’s own wood. I hope you enjoy its delightful tale, one of love.

I visited Marilyn Hauke, a descendant of the Sauner line, after whose grandfather the Hillsboro street Harry Sauner Road is named. At 91, Marilyn’s mind is still sharp and her demeanor reeks of affluence. “I was born with a silver spoon, honey, but I married a wooden one,” she chirps.” She cautioned me, “Honey, you won’t write anything bad about me, will you?” And then, “Well, maybe not so bad.” A sense of humor seems to prevail in the 90-year-olds I’ve met. Maybe that’s their secret.

Marilyn owns the barn and the farm, along with a nephew – as well as the one where she lives, which is called White Oak View Farm. She has a herd of 30 registered Angus cows. Her husband, the love of her life, Vic Hauke, died at 73 in 1994. She’s been a widow since then.

This story begins around the time of the Civil War when Harry Sauner’s father owned a lot of land in Highland County. About five miles of it. How? A Civil War grant? They had eight children and were able to give each of them a farm from their vast land holdings. What a nice start in life: a farm with acreage.

Fast forward to around 1900. Marilyn showed me a photo of three men in suits, standing confidently next to three Model T Ford cars and under a large sign, “Ford Motor Cars, Miller and Sauners.” Ford produced its first car, the Model A, in 1903, and in 1908 the company rolled off its first Model T, a car that revolutionized America since it was affordable to many in the middle class and apparently that market extended into Highland County. The Miller-Sauner dealership was originally in Mowrystown, but after they sold it, it moved to Hillsboro.

Harry Sauner married Stella Miller and went into the car business with her father. They also lived in Mowrystown. They had one child, Gladys, Marilyn’s mother, who married Ferry Roberts, a farmer. An only child to parents of wealth, Gladys, as Marilyn put it, was spoiled.

Marilyn was born in 1925 in the height of the roaring ’20s, an era when America prospered. Farmers were doing well, as were car salesmen. “So, Marilyn,” I asked, “what was life like for you during the Great Depression?”

Her reply, typical of most 90-year-olds still alive in farming communities, was simple: “I never knew there was a depression.” But then came, “We went to Florida in the winter.” Now, this vacationing in Florida wasn’t for a week or two, nor for two or three months. No, Marilyn and her parents spent the entire winter in Florida – five months of it. Translated: money.

In 1929, Marilyn turned 4. She remembers spending those warm winters with her parents for several years before she started school. Where? “We rented a tourist cabin at first, but then we bought a home on Daytona Beach.” What happy years for a youngster: farm life in the summer and fun on the beach in the winter.

But in the ‘30s she became old enough for school and learned what Ohio winters could do. Marilyn told me that for three years she walked down the road to a one-room school house, a chilly journey in January. Eventually she moved on to high school, though she still vacationed in Florida when the family could go there. These were gloomy years for America. But Marilyn’s family did just fine and she grew up affluent, with the understanding that she would go to college and marry a young man, one who was educated and from an equally affluent family. At least, that’s what her mother wanted.

In those years Florida played second fiddle to Jekyll Island, a small dot off the southern Georgia coast, was where the real money was in the 1920s – a haven for the Morgans, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts, and other influential Americans who founded the famous Jekyll Island club, dating to the late 1800s. At one point, one fifth of the world’s (not just America) wealth belonged to this club. In 1910, they started the Federal Reserve there. Florida was not popular, especially after the 1925 real estate bubble hit, leaving entire cities and other projects bankrupt. Add the depression of the 30s and the fruit fly disaster. Florida was a mess. But that changed in the 1940s. The big money left Jekyll, their mansions, and moved to Florida. Marilyn had other ideas.

While her parents spent half the year in Florida and Marilyn went to school, she lived with her grandparents, Harry and Stella, who treated her like a queen. She spoke fondly about them, especially about her grandmother. And, by the time she became a senior in high school, she had made up her mind. She wasn’t going to college; she was going to marry Vic. With or without mom’s approval. Her mother knew Vic and didn’t feel he was from “the right family” and simply wasn’t good enough for her daughter. But Marilyn was in love.

So, a few days after Marilyn graduated from high school, Marilyn and Vic told her parents that they were going to Cincinnati’s Moonlight Gardens for a few hours of fun and dancing. “We’ll be home late,” Marilyn told her mom. “What a lie,” Marilyn told me. They didn’t return that night. That was 1943. War time. Marilyn was 18. Vic was a little older.

Moonlight Gardens is still operating in Coney Island. Ironically, the person who started the park was not a Cincinnati businessman but a farmer, an apple farmer named James Parker, who bought a 20-acre apple orchard in 1867 and eventually rented it out to Cincinnatians for picnics. He later added a dancing hall, dining hall, bowling alley, and even a mule-drawn merry-go-round. Twenty years later he sold it to a group headed by two steamboat captains who renamed it “Ohio Grove, The Coney Island of the West,” hoping to draw attention by naming it after the famous Coney Island in New York. They charged 50 cents for an hour-long boat ride that took passengers away from the crowded hot city to a haven of fun for a day.

Over the years the park added Ferris wheels, wooden roller coasters, bumper cars, and many other rides to entertain children and their parents. But the dancing continued and in 1925 a Philadelphia company built Moonlite Gardens, an open-air dance hall, and Sunlite Pool, an architectural feat in itself, still the world’s largest re-circulating swimming pool – so large it can hold 10,000 swimmers.

But the Great Depression took its toll, as did the great flood of 1937, submerging Coney Island under nearly 30 feet of water. Then World War II hit, taking men and women into the military and making all Americans bond together in an effort to stop the Germans and the Japanese. The park survived, and even though war rationing curtailed visitors, those affluent enough could still drive to the park, which is what Marilyn and Vic told her mom they had planned.

Instead, they got married. Not in Ohio, not in front of a well-dressed throng of well-wishers, not with a six-layered wedding cake. Instead, they drove across the Ohio to lowly Erlanger, Ky., where they knew two young kids wouldn’t have any trouble getting married. No questions asked. One of Vic’s neighbors knew a minister there and he arranged the trip. Marilyn packed her suitcase and snuck it out of the house to Vic.

Northern Kentucky, and Newport especially, in the 1940s, had become a den of iniquity. Gambling halls, seedy nightclubs, prostitution, brothels galore. Cincinnatians called it “Sin City,” though they frequented those attractions for 40 years. The mob was alive and well in Newport – from the days of prohibition up until the 1980s. In the 1940s the “syndicate” – headed by New York’s infamous Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano – had its hooks in this town. It was a money maker. But it was also a place for two love-struck teenagers from Hillsboro to get married, which they did in nearby Erlanger.

Gladys must have worried when her daughter didn’t come home that night. Where was she? And why did she go off with that boy she didn’t like? It must have been a sleepless night for her. And Marilyn, not wanting to fan the flames, didn’t call her. Instead, she called Stella, her kindly grandmother, to tell her that she married Vic. She figured grandma would be a bit more receptive to the news and she was right. Marilyn made the call from the Netherland Plaza Hotel, Cincinnati’s premier hotel in the 1940s, listed today on the National Historic Register. A story in itself, the hotel almost didn’t happen.

When the Emery family of eastern Cincinnati, wealthy from processing pork and other stockyard products, got the idea for a fabulous hotel and a skyscraper (the Carew Tower) in the late 1920s, they approached banks for financing, but were turned down. So in 1929 – before the stock market crash – they sold their stocks and financial investments and financed the buildings with their cash. Their legacy endures today – in one of America’s most beautiful hotels and a Cincinnati skyscraper.

The hotel was a perfect place for a honeymoon for two young newlyweds from Highland County. And it must have dazzled them: seven restaurants, an incredible chandelier in the Hall of Mirrors, a big-band nightclub – one that featured the professional debut of Doris Day – and even an ice-skating show in the ballroom. Vic must have saved his money: he paid for everything.

After a short stay in the hotel, Marilyn and Vic returned to Highland County, high school grads and married. Since Marilyn had lived a charmed life, she had to learn to be a wife. “I never even knew how to mash potatoes,” she told me. But she learned. Vic’s mom accepted this child of wealth, taught her how to be a mother, and showed her how to cook. And Vic, from humble roots, was a hard working farmer as well as a brick and stone mason. They survived, raised five children, put them through college, and had a good life. They had been married for 55 years when Vic died at 73.

I didn’t have to ask Marilyn if she had made the right choice in fabricating the Moonlight Gardens story, eloping, passing up a fabulous wedding, and marrying below her economic level. All of a sudden, she blurted, “I’d do it again in a heart beat.” Yes, she’d marry Vic again – without hesitation. As the French say, “C’est l’amour.”

Robert Kroeger is a former Cincinnati area dentist who has since ran in and organized marathons, took up the painting skills he first picked up from his commercial artist father, become a published author, and is a certified personal trainer that started the LifeNuts vitality program. Visit his website at http://barnart.weebly.com/paintings.html.