Editor’s note — Following are the recollections of Christopher S. Duckworth, a longtime Ohio Historical Society employee with family ties to Hillsboro and Greenfield, after he found a 108-year-old photo album belonging to his grandfather.

Alexander Morrow (1788–1827), the father of our subject, was born in Pennsylvania and served during the War of 1812. His father, John, had fought in the American Revolution.

In 1815, in Highland County, to where the Morrow family migrated from Pennsylvania, Alexander Morrow married Mary Coffey. The couple had one child they named William Alexander Morrow. He was born in Greenfield on May 13, 1826. Less than a year and half later, Aexander died, leaving Mary to raise William. In her remaining 50 years, Mary never remarried.

We know very little about William’s life growing up. One may imagine that he reached maturity in typical fashion for a youth of that day and in that place. Then his life changed as he discovered a new profession and a new love.

In 1839, French artist Louis Daguerre published the first viable process for capturing a permanent image using a camera and lens along with a chemical process. The worldwide reaction was astonishing as people rushed to have their images captured. With incredible speed, daguerreotype studios sprang up everywhere, especially in the United States. By the late 1840s, every American city had a studio while scores of other daguerreotypists drove wagon-studios to smaller towns and villages. By 1850, thousands of American daguerreotypists were taking an estimated three million portraits annually.

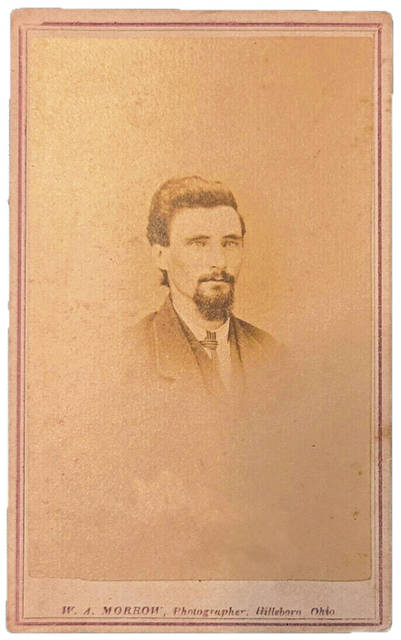

Precisely when and where William Alexander Morrow first saw a daguerreotype and committed to make photography his life’s work we do not know. But in 1850, he told a census taker that he was a “Daguerrean artist.” The young man clearly had chartered his course beyond his new occupation. In Chillicothe on Jan. 8, 1852, he married Harriet L. Taylor. The union was a happy one. The couple were married for 54 years, ended only by William’s 1906 death in Hillsboro. They parented nine to 12 children — the number varies depending on the source — seven of whom survived their father.

In June 1863, however, Morrow’s carefully planned life was jarred when he had to appear before a conscription board to determine his suitability for a Union Civil War draft. He received a “II” classification and was not conscripted, probably because he was married with six dependent children. Unlike his father and grandfather, William Alexander Morrow never entered military service.

William and his growing family moved from Greenfield to Chillicothe, and then to Marietta as he established himself as a well-qualified photographer. He also transitioned from the daguerreotype to the then-new wet-collodion, or wet-plate, process that had been invented in 1851, also to worldwide acclaim. Ambrotypes and ferrotypes (popularly called tintypes) were popular wet-plate products. Like the daguerreotype, both yielded unique direct images — not unlike the Polaroid in principle if not technology. Neither an ambrotype nor a ferrotype can be linked to Morrow, perhaps because few of either commonly bore the photographer’s imprint.

In addition, the wet-plate process was the first to yield a negative, which could be printed onto photographic paper to make positive prints. For the first time, a photographer could produce multiple prints from a single exposure. Morrow mastered the negative-positive process and became a very successful studio owner and operator.

On Christmas Eve 1863, Morrow announced the opening of his Sky-Light Gallery. His new photographic emporium, located on the second and third floors of a building on East Main Street, featured a lavish reception area replete with “new carpets, furniture, and so forth.” His studio’s most impressive and important feature was the third-floor “operating room” — the studio where portrait-taking took place. The ceiling and probably a sidewall featured “a very large sky-light window… affording the best possible light for the mysterious and truly wonderful process by which the sun is made to paint the lineaments of form and feature.…” This reporter further lauded Morrow not only for having “the best facilities,” but also because the photographer possessed “long experience and skill.” He was, the reporter wrote, “a popular Daguerrean artist and photographer.”

In March 1878, after a quarter-century as a successful photographer and gallery owner, Morrow relinquished his Sky-Light Gallery for health issues. He and his family moved to a more relaxed life as “a farmer living near Winchester in Adams County.” He sold the Sky-Light Gallery to L. Newton Langley, who promised a “highlighted style of the art.” Langely, however, operated the studio for only a year before selling it to English-born William H. Downing, who became a successful photographer before he sold the business in 1889 and with his family moved to Cincinnati.

After a few year’s respite in the country to regain his health, Morrow returned to Hillsboro and established a studio in the Bell block. In March 1886, he abandoned that studio and took charge of the Elite Gallery located on North High Street “opposite the new jail.” He advertised that he “would like to see all his old patrons” and promised that “all new ones will have a hearty welcome.” Once again, William Alexander Morrow was an important player in the Hillsboro photographic scene.

Morrow left the photography business permanently to become a fire insurance agent. Perhaps the competitive nature of photography or perhaps the rigors of the studio and darkroom prompted him to do so. At one point, he and Harriet shared their home with 10 of their children. If unremarkable, the couple’s life was comfortable as they were surrounded by family.

A quarter century after leaving his remarkable Sky-Light Gallery, William Alexander Morrow died on July 7, 1906. The newspaper placed his obituary on the front page and eulogized him as “One of Hillsboro’s Oldest and Most Respected Citizens.” Seven years later, Harriet joined him. They rest side-by-side in the Hillsboro Cemetery alongside their daughter Jane.

Far from being forgotten more than a century after his death, Morrow’s name survives on myriad photographs.

I became interested in Morrow when I found his imprint on images in my collection. Yet, the more that I researched him, the more confused and frustrated I became.

Contradictory, conflicting and confusing facts abounded. Greatly exacerbating the situation, William Alexander Morrow was not the only William A. Morrow in this area at that time.

William Augustus Morrow also appears frequently in numerous records — from census surveys to newspaper articles. The two, Alexander (1826–1906) and Augustus (1827–1913) closely shared life dates and other matters of public record. In those days, full middle names often were not listed — in this instance, almost never. They lived in proximity — probably they even knew one another. Both were successful businessmen. Home on North High Street: Augustus. Home on East North Street: Alexander. Thirty-year secretary of the Hillsboro Cemetery: Augustus. Father of George Morrow: Alexander. Formerly of Lynchburg: Augustus.

Regardless, two William A. Morrows living at the same time and in the same area makes for difficult research and a rather frazzled researcher. However, I remain convinced that further research will reveal much more about both men.

Just the story of photographer William Alexander Morrow, as is the case with many 19th century photographers, is replete with gaps and contradictions. Please add confusion to this instance.

In my six decades of historical research, this is perhaps the most perplexing research project that I have encountered — and that includes tracking down several 16th century settlers.

The stories of William Alexander Morrow and William Augustus Morrow beg for additional research. I fervently hope that what I have found will assist future researchers as they unravel the Morrows.

Christopher S. Duckworth spent three decades at the Ohio Historical Society, where he was founding editor of Timeline magazine, followed by another 10 years at the Columbus Museum of Art. Today, he owns his own publishing company, Brevoort Press LLC.