This is a photo inside Bell’s Opera House looking toward the stage from the lower seating level with the balcony above.

Times-Gazette file photo

This photo shows the exterior of Bell’s Opera House in Hillsboro.

Courtesy photo

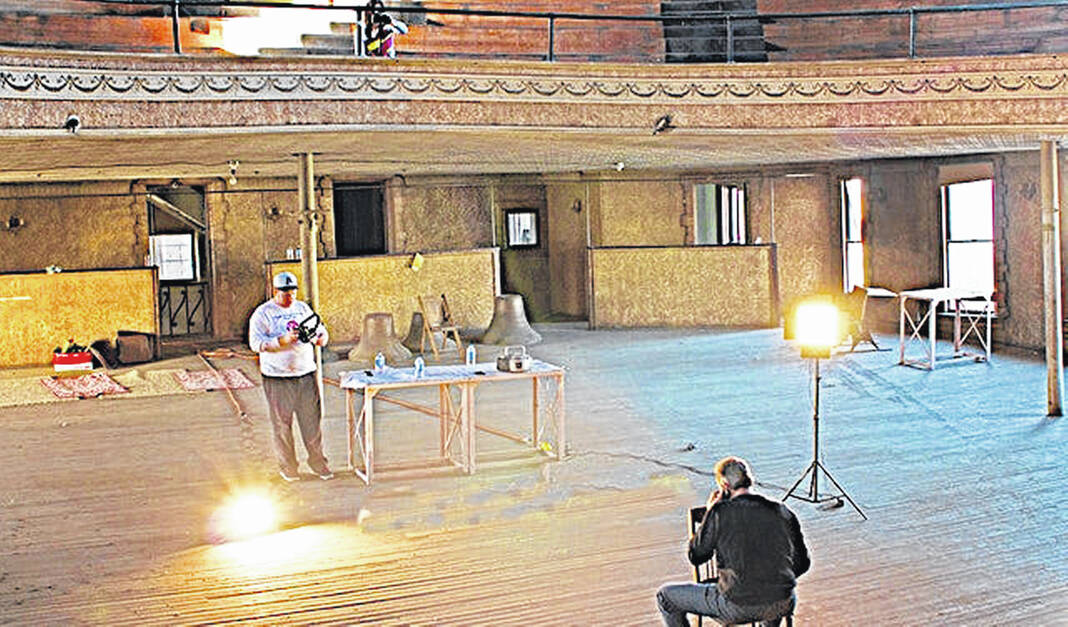

This photo shows the interior of Bell’s Opera House looking toward the balcony when a music video was made there a few years ago.

Times-Gazette file photo

With its rufescent exterior facade, momentous height, skyward jutting spires and a distinctive cupola, Bells Opera House on South High Street in Hillsboro is one of the small Midwestern town’s most well known, inspirational and beloved historical buildings and landmarks.

Beyond its stunning physical presence and vastness, the building is also a source of interest for people who are fascinated by its past, present and future.

The imposing structure encompasses, “half a city block,” according to narration by current owner and former Hillsboro Mayor Drew Hastings in a YouTube video in which the history and present condition of the iconic venue is explored in intricate detail. Hastings provided a virtual tour in the video of much of the interior historical minutiae inside the building.

Through these vestiges, the viewer is invited to imagine another time during which people, “from all walks of life” gathered regularly to enjoy live entertainment in the days before movies, and how such a place could be repurposed in a time in which we can hold movies in in our hands.

Ever the raconteur, Hastings described in the video everything from the historical significance of the establishment, to his acquisition of the building in more recent years, to all the salient details that could be of interest.

Among these is the fact that according to the video, at one time the manager of the Opera House concurrently ran an insurance business whilst attending to matters pertaining to the theatre. As a result, much of the paperwork from that business remains, essentially untouched, in one of the offices upstairs.

Another comes in the form of the theatrical ephemera that is scattered throughout the facility. Hastings revealed in the video that actors and technicians would leave graffiti and inscriptions on the walls behind the curtain that indicated their presence there. The signatures and messages that indicated, “We were here,” span decades in the early twentieth century, and Hastings speculated that it might have been a nascent form of social media that allowed performers to pre-emptively communicate with other people in the entertainment industry who would be performing there later. Hastings remarked that, “So it’s really interesting and amazing that this stuff has survived all this time…” as he read the truncated messages transcribed over 100 ago that still adorn the walls.

The opera house also contained the remnants and advertisements of past shows of live entertainment which had ranged from an on-stage “barn dance” to a “scandalous” can-can-girl or risque burlesque style revue and other ragtime era and Jazz Age dance genres that were popular then. The multiple archived advertisements for shows that played at the opera house constitute an awe-inspiring, time-traveling dive through the annals of live entertainment history of the country in the early years of the twentieth century. Ads for the, “Big Jazz Opera” with the “Fastest Stepping Chorus In America” might conjure images and sounds of the musical echoes that once reverberated through the opera house.

Vaudeville was a popular sort of entertainment with advertising that described, “High class singers, dancers, and comedians” at the opera house.

“There was something for everybody,” Hastings said in the video.

Indeed, true to the purpose that motivated its fast track building, completed in 1895, following less than a year of construction time, Bell’s Opera House was a place of congregation and entertainment for everybody, regardless of social class.

It seated 1,000 people, “which was a lot for that time,” Hastings said.

“You had farmers that would come into town. Wealthy people who lived in town. Working class people who couldn’t afford much. You had anybody and everybody,” he said.

The only nod to privilege was the elaborate box seats flanking the stage, one of which was customized for C.S. Bell, whose name the building bears, and without whose philanthropy it would not exist.

Of the intended denizens of such exclusive seating, Hastings remarked, “They wanted to be seen by the audience just as much as they want the stage show to be seen.”

“So it was a bit of an ego trip,” he said of the box seats. They have since been covered with a decorative background.

Though the lower level seats have been removed, Hastings described how things would have appeared at that time, and where the orchestra pit performers would have played their musical accompaniments before the advent of recorded sound.

Other indicators of the past that sparked conversation included an old breaker box, no longer in use, that illustrated the limitations of the era’s technology and electrical wiring.

Years before Hastings acquired the property, a cadre of concerned citizens formed a dedicated preservation organization, called the Highland County Preservation Group (HCPG). Spearheaded by realtor Christina Ross, their goal was to preserve the historic opera house.

To this end, the group’s contributors published a monthly newsletter entitled, “A View From The Tower Windows,” which detailed not only their efforts toward and hopes of a acquiring and restoring the property, but its vast and noteworthy history.

Prior to being purchased by Hastings it was owned by the Gordon family, who had been proprietors of an auto parts store located on the ground floor of the opera house. The Gordon family acquired the property from its previous and original owners, the Bell family. With its subsequent purchase by Hastings, the property has had but three owners during its existence.

“We always hoped for restoration of the actual opera house,” said Avery Applegate, who was involved with the HCPG, “but we were most concerned with the preservation of the building. Lenore Gordon put a new roof on the building just before she passed away.” Applegate said that its former owners recognized the importance of such in maintaining the integrity of historical structures such as the opera house and others.

Bell’s Opera House was one of a many of a spate of opera houses in the Midwest that were constructed around the same time period to accommodate the need for public entertainment. Before Netflix, social media, the Internet, TV, movies or electricity, the opera house provided a platform for the live performances by which people were frequently entertained in those days.

“This was the original multimedia center of its time,” Hastings said.

During the height of its popularity, which lasted more than a decade, “They put up shows, and everything was fine,” Hastings said.

Until movies came along.

“Something called movies came out,” Hastings said, “and that was a big problem for opera houses.”

Technology, and specifically the invention of the motion picture, proved to be disastrous for such venues as the public’s interest in live performances began to wane in favor of its fascination with film as a new and exciting form of entertainment.

Another contributor to the theatre’s obsolescence was the building of a new high school in the 1930s. Before that time, the opera house not only hosted theatrical productions and dancing girl revues, but served much as an auditorium might for high school graduations and other ceremonies. Once the high school had its own facilities, those offered by the opera house were no longer needed.

According to the video, the opera house began in the nineteenth century, presenting theatrical productions illuminated by gas lamps until being later retrofitted with electricity when that technology became more commonly available. “It was not a safe way to do it but that’s the way it was done at the time,” Hastings said in the video. “Obviously, there have been improvements since that time.”

When movies came along the theatre tried to accommodate the public’s newfound interest by adapting the theatre to that medium, however futilely.

It didn’t help matters that even as Bell’s Opera House attempted to adapt to changing consumer trends and show movies, competitors started cropping up in town. John Glaze of the Highland County Historical Society said that his mother said that in Hillsboro during the ’30s, people took advantage of the theatrical competition at their avail locally. “They used to go to a movie at Bell’s, then to the Forum,” he said.

“The Great Train Robbery” was reportedly, in 1901, the first (silent) movie that was presented at the opera house.

By 1930, synchronized sound films were the trend movies like “King of Jazz” were being advertised at the opera house.

Another invention — the automobile — also likely contributed to the demise of the business opera house as it became easier for local citizens to seek entertainment elsewhere.

Despite changing times and technology, Bell’s Opera House, its history and potential, is still very much of a topic of interest. Historians such as Max Petzold, entities like the Highland County Historical Society, and others have curated a vast collection of information about the building and the time during which it was built.

Former HCPG member Darin Schweickart, who documented much of the group’s plans and endeavors for its proprietary publication, said that the group had, “wanted to restore it,” but its, “main goal was to prevent it from deteriorating.”

In retrospect, Schweickart acknowledged that, “the problem is still the same as today. It’s not as much of a problem of raising the money to restore it. It’s what you would do to sustain the building should it be remodeled. A theater is nice, just not a money maker in Hillsboro.”

According to historical records, when Bell’s Opera House was originally planned, C.S. Bell, who, in addition to running the C.S. Bell Company was involved in other business and government ventures in Hillsboro, secured the lot on which Bell’s Opera House now stands, but challenged the town’s residents to raise $3,000 (about $100,000 today) with Bell conditionally acquiescing to cover the rest.

The total cost ended up being $40,000, which is roughly equivalent to $1.5 million in today’s money.

True to their word, the people came through, the money was raised, Bell kept his promise, and the opera house was built.

Bell not only financed but was in charge of the construction of the building, according to historical records, and facilitated any necessary upgrades.

“When the building needed upgraded sewer systems” that Hillsboro did not have at the time, “He paid for that work also,” said Glaze. “When things were slow” at the bell company “he would send some of the men up to the construction site. The bell company workers would, “help with the construction” of the opera house.

Less than a year after the clearing of a dilapidated lot that was dotted with makeshift shanties often referred to as “Rat’s Row,” the opera house opened to much fanfare and its first showing was of “Friends”, a comedy-drama by Edwin Milton Royle.

The following evening, a four-act production entitled “Mexico” was presented at the opera house.

With 1800’s technology and a lot of money and determination, the dream of a performance venue became a reality.

During its 1902 season with C.S. Bell as proprietor and F. Ayres as manager, Bell’s Opera House proclaimed via pamphlet that, “This house is intended to be a place where ladies and gentlemen can spend an evening pleasantly, and free from the annoyance of the unruly. Therefore, the use of tobacco, unnecessary noise, such as whistling, screaming, stamping of feet, or any other unbecoming conduct, is forbidden.”

Bell’s Opera House received a National Register of Historic Places designation in 1980.

Juliane Cartaino is a stringer for The Times-Gazette.