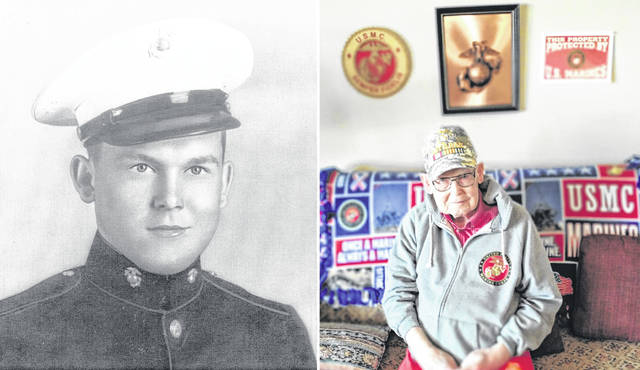

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part profile on Highland County native Robert Wayne written by Paul Butler originally for the News Journal in Wilmington.

The little farmhouse just outside Samantha, Ohio was filled with joy as the Caldwells — Harold “Squibb”, Elizabeth and 2-year-old Dean — welcomed the newest addition to the family, Robert “Bob” Wayne.

Unfortunately, the joy of that 26th day of May 1925 only lasted a few short years. The young family was devastated by events and circumstances beyond its control.

Harold, a dairy farmer, became stricken with crippling arthritis. The nation was stricken with an unimaginable economic crisis: the Great Depression.

Elizabeth had to go to work and the boys had to move in with their maternal grandparents on their 135-acre farm.

No running water in the house meant Bob’s number one chore was hauling water for his grandmother from a nearby spring. He also had plenty of other jobs around the farm, but somehow, Bob always found time to trap muskrats and rabbits and, a few years later, hunt with the rifle he was given for Christmas.

Like brothers

Growing up, Bob became fast friends and some even said like brothers with another local Robert, Robert “Bobby” Crites; always together, they were known throughout the small community as Bob (Caldwell) and Bobby (Crites).

They did everything together. So, when they were in grade school and the opportunity arose to go to Washington, D.C., neither wanted to go without the other, but Bobby’s single mother could not afford the train fare.

Somehow, the irrepressible Elizabeth Caldwell came up with the $35 needed to send Bob, Bobby and his mother, Mildred, to the nation’s capitol. No money for a hotel and little to spare meant that the three spent nights in the train station eating bologna sandwiches and rehashing the day’s adventures.

The boys preferred hunting and trapping to school, especially Bob, whose mother had made a deal with him: “If you complete your education at Leesburg High School, I will give you my gold watch.”

In high school Bob joined the Guard, accumulated enough credits to graduate early, and decided to enlist in the Army like his brother, Dean. The older sibling, who had been assigned to the “Tank Corps,” injured his leg and received his discharge after only six months of active duty.

Confronted with the pending enlistment of her boy, Mrs. Caldwell reminded him of his Quaker upbringing and its teachings. She said: “Son, you know you don’t have to go.” To which Bob replied: “I would not want someone else to go in my place.”

The young Caldwell could not end the conversation there. He had to add: “You know how I feel about those fellows that dodge the draft when their country needs them.” Mrs. Caldwell knew Bob had made up his mind and further discussion would be futile.

In the Corps

Since the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Bob had wanted to join the military.

Now, as he stood in line awaiting his turn to take the Army’s mandatory physical, he almost had to pinch himself — bigger than life in front of him stood a sergeant in the United States Marine Corps, wearing the “sharpest” uniform Bob had ever seen, asking the young men in line: “Who wants to be a Marine?”

The young Caldwell could not answer in the affirmative quick enough. He and another fellow stepped out of the Army line and headed down a long hall to get a Marine physical.

While waiting his turn, Bob observed the young man who had accompanied him in departing the previous physical line, sobbing as he exited the room where the physicals were being conducted. Caldwell asked him, curiously: “What’s the matter fella?”

The sobbing young man looked at him through tearful eyes and moaned: “I failed!” and scampered back down the hallway toward the Army line. That scene replayed itself in his mind as he rode a crowded train for four days and four nights, stopping three times a day for everyone to disembark — get something to eat, stretch, and then go back to a cramped seat — to San Diego, California and Camp Pendleton for basic training.

The basics

The U.S. needed more men on the battlefield badly, so they shortened basic training from 12 weeks to eight. Certain disciplines were eliminated from the training, but certainly not firearms training.

Platoon 114, which included 18-year-old Caldwell, marched up the hill to the firing range where his many days of tromping through the brush, hunting, paid off.

When 114 was finished firing, Pvt. Caldwell was declared an expert marksman. Later that evening, after reviewing the targets, it was determined that Caldwell had actually qualified as a “sharp shooter.” It was not just an empty title: with it came a $5 a month raise in pay, bringing his total monthly compensation to $55.

Caldwell’s boot camp company was 70 men strong upon graduation from its eight weeks of intensive training. Sixty-six were assigned to the 5th Division and four, including Caldwell, were assigned to a Replacement Detachment at nearby Camp Elliot.

Bobby’s sacrifice

Back home, Robert “Bobby” Crites graduated with the Leesburg High School class of 1944, followed almost immediately by Marine Corps Boot Camp some months after Bob Caldwell, and upon graduation, was assigned to the 5th Division. The Replacement Detachment to which Bob Caldwell was assigned had been on Guadalcanal and was now headed to another island, another battle.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Division, which included Bobby Crites, deployed to a different island for one of the bloodiest and most costly battles in terms of the loss of “American Treasure” — 19,217 wounded and injured, and 6,871 killed in just 37 days (Feb. 19 to March 26, 1945).

On the 11th day of March 1945, 14 days before the Japanese surrender, Pvt. Robert Baker Crites, 986784, USMCR, made “the supreme sacrifice” for his country on a volcanic protrusion of lava in the Pacific Ocean called Iwo Jima.

To Okinawa

As the fighting on Iwo Jima was winding down, Caldwell, unaware of Bobby Crites’ death, was onboard a U.S. Navy ship being transported, post haste, to Okinawa, where he encountered the fiercest fighting he saw in the war.

During the amphibious landing, Bob felt a sting on his knee, but didn’t “think it was a big deal,” so he kept on going, not realizing he had been nicked by a piece of shrapnel from the strafing that greeted their arrival.

This was just the beginning of the close calls, death and devastation the 19-year-old from Samantha witnessed during the next few months.

Part 2 will appear in tomorrow’s Times-Gazette.

— — —

The writer of this series, Paul Butler, is a Wilmington resident, U.S. Navy veteran, and a class of 2020 inductee in the Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame. Last September, Clinton County recognized Butler for his “dedication and commitment in military service as well as his exceptional post military advocacy and volunteerism for the veteran community.”