The smile eased over the face of young grandson, Jack, the first time we did “the talk,” as we call it. Sometimes we discuss school, or current events, and other times we peek into the past and chat about the old times.

This is what we looked at during our visit with Jack last Saturday in Lexington, Kentucky. He is 16 years old now, and he has a job.

Our formative years couldn’t be more different had Hollywood written the script.

Jack is a product of the big city. He has lived all his life in Lexington, attending elementary school in the heart of downtown, where the commotion of the urban lifestyle flourishes. He first rode the city bus alone when he was 13, with a broad mixture of characters, and the sounds of the hectic metropolitan downtown swirling all around him.

I grew up in Port William and Wilmington. He loves for me to explain to him what it was like growing up in the small towns.

“Grandpa, why are you called a Baby Boomer?” he asked.

“Well, because I was born when everything was booming after the Second World War. The economy was booming, births of babies were booming, schools and houses were booming,” I said.

“Jack, small towns are people, and people had different values then. We knew everyone in town. My grade school class in Port William had only 20 students. In the summer, the Port Lions Club showed outdoor movies on a big blanket downtown,” I said.

“Do you remember the Beer Joint in Port William?” he asked.

I knew what was coming. He wanted to hear the story that was so foreign to his way of life in 2022. Looking back, it is hard even for me to believe it ever happened, but it was a different time.

“Jack, a block from the mill dam sat Jim Edwards’ Café, between Julia’s Restaurant and Stephens Hardware. The locals called it the Beer Joint. Jim Edwards served hot food, soft drinks and cold beer, and it was a place where townsfolk, farmers, and students gathered to eat a hamburger, drink a beer or enjoy a cool glass of cream soda.”

“Did they really let you inside when you were only 8 or 9 years old?” Jack asked.

“Yep, they sure did,” I replied. “It was a different time.”

My parents didn’t believe having their young son mingling with friends of the family, although many were beer drinkers, was going to corrupt him.

I warmed to the story and Jack smiled.

“One regular customer was an elderly farmer who had retired from the farm and moved to Bowersville. Late in the summer of that year, he died. His teenage son buried him in a cornfield on their farm,” I said.

One afternoon, about five o’clock, when the farmers were out of the fields and the factory workers had returned from Dayton, I was sitting in the Beer Joint with my uncle.

The farmer had been dead for about two months when his young son walked into the tavern. None of the men knew him, because, unlike his father, he wasn’t a drinking man and had never been inside the bar before.

The young man whispered into the ear of one of the other regular customers.

The man nodded. He stood up and said, “Fellows, may I have your attention for a minute? This young man wants to say something to us.”

The men quickly whirled around on their bar stools and looked at the boy.

“My daddy, whom many of you knew, died a while back and we buried him in his favorite field out next to the corn crib. I got to thinking about the situation and decided to come talk with you.”

The boy continued speaking. “I don’t have any money. I lost my arm up to my elbow on the corn picker last fall and can’t work for a while. My dad doesn’t have a tombstone for his grave. The wooden cross that I put up doesn’t seem right. I would like to get him a nice headstone. I’m not a religious man, but my daddy was, and I know he wants to get to Heaven. I think a headstone would make sure he isn’t forgotten.”

The men grew quiet. His words had pulled and tugged them along. Then Jim Edwards spoke up and wrote a check for $100. He took off his hat and passed it around.

As the hat reached the end of the line, they handed it to the young man.

“Three-hundred dollars! I can’t believe it!” He laughed, then suddenly began to weep.

A few weeks later, the men learned a gray tombstone stood out where the corn was tall and green.

Jack began to smile. “Dang. That sure is different from Lexington,” he said.

“It was a different time,” I replied. “A very different time.”

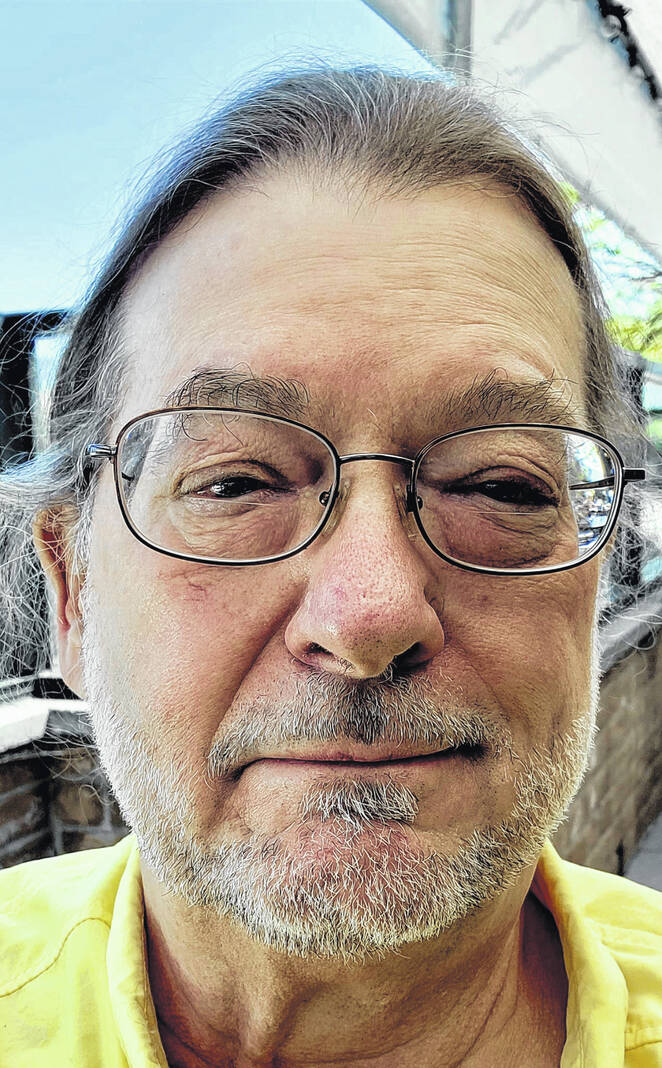

Pat Haley is a Clinton County native and former county commissioner and sheriff.